By Walter Fieuw (on behalf of CORC/uTshani Fund)

South Africa celebrates two decades of independence this year. It is also a decade after the then-Department of Housing issued its guiding framework document, Breaking New Ground (BNG): A Comprehensive Plan for the Development of Sustainable Human Settlements. Since 2004, when BNG was introduced and all subsequent National Housing Codes were amended to give meaning to the concepts and principles contained therein, we have experienced escalated protests in informal settlements around the country. These “service delivery protests” are often in response to lack of basic services. Politicians claim to have radically improved access to water and sanitation, but these claims can not be validated, and the devil lies in the detail. Its a critical time to reflect on housing praxis ten years after Breaking New Ground, and in this blog post we consider Part 3 of the National Housing Code: the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP).

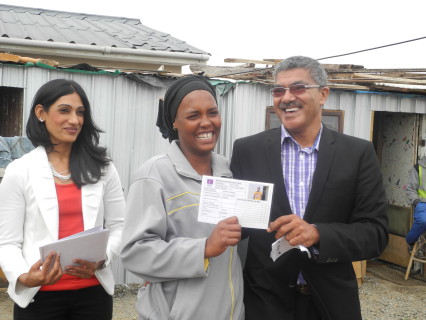

Never before has civil society, urban sector NGOs and new state institutions been as interested in the upgrading agenda. An example of this was the Isandla Institute and African Centre for Cities conference in 15 and 16 October 2013 titled ‘Partnership-Based Incremental Upgrading of Informal Settlements in South Africa’. ISN and CORC, as part of the South African Alliance linked to SDI, have made strides in upgrading and have received a number of awards for its work in Langrug, Stellenbosch Municipality (UISP Phase 3) and Mtshini Wam (incremental upgrading). Other social movements such as Abahlali baseMjondolo traditionally lobbying only for housing and land have also called for alternatives, of which settlement upgrading and governance reform are primary.

UISP in retrospect

UISP has been through various iterations since 2004, with major amendments in 2007 and 2009. Academics such as Marie Huchzermeyer has called attention to various progressive elements of the policy being removed. Part 3 of the National Housing Code (2009) argues that informal settlement upgrading is ‘one of the Government’s prime development initiatives and that upgrading projects should be dealt with on a priority basis’ (DHS 2009:25). However, the application of UISP before the establishment of National Upgrading Support Programme (NUSP)[1], Outcome 8 of the Presidency, and perhaps to a lesser extent Chapter 8 of the National Development Plan has been extremely weak.

There has also been varied interpretations on how UISP should be applied to different types of informal settlements. Cape Town, as an example, illustrates this point, and two examples – one quite bottom-up, participatory and empowering, and the other top-down and “modernist” – are worth considering. Hangberg in Houtbay was one of the City’s first UISP projects. It had all the right elements to make it a successful upgrading: strong and transparent community leadership and structures, mediation and capacity building by an urban sector NGO Development Action Group, and a strong political will by the City’s mayor and line departments. After moving through Phases 1 and 2, the project broke down in draconian police violence in 2010. Ever since, there has been little progress. The other example is the N2 Gateway Project, which was also packaged as a UISP. Here government departments eradicated the Joe Slovo informal settlement in 2004, moving many residents to Temporary Relocation Areas (TRA), to stabilise and rehabilitate the land. The project was challenged in the Constitutional Court, and the state was forced to house the relocated families. Needless to say, many still remain in the TRAs.

Often times its not so much about the “What?”, but about the “How?”. The UISP does not yet solve many of the complex issues that informal settlements represent, since it falls back on very linear logics. If the UISP were to be restructured, it needs to consider the following themes, which is followed by more practical recommendations for restructuring the programme.

Themes to be addressed by the UISP

Theme 1: Partnership approach: Most Metros, where the majority of informal settlements are located, have been accredited as housing developers. The City’s role as the developer is essential, but local democratic structures need to be create to facilitate effective upgrading. There should be a stated recognition and budgetary allocation to allow for intermediary support, such as NGOs, community networks, organisational development consultants and mediators (in conflict cases). Without intermediation, the ideals and goals of developing partnerships will remain rhetoric with no execution power.

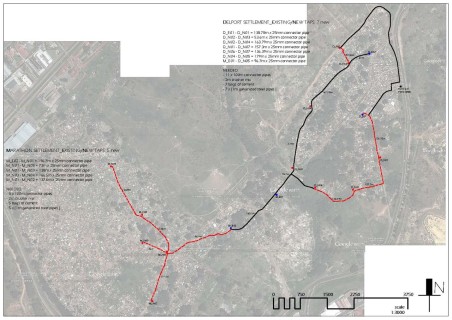

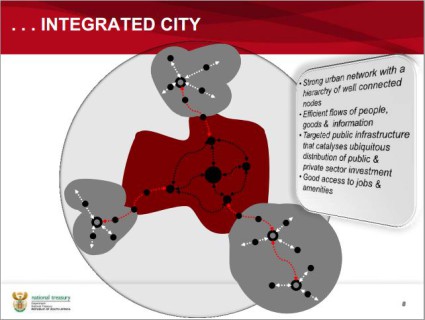

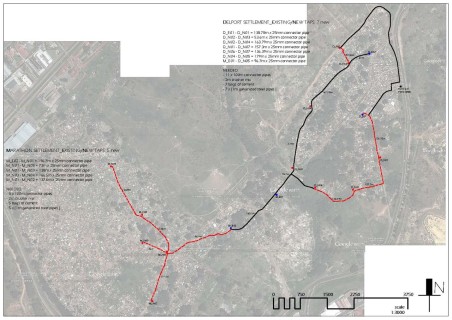

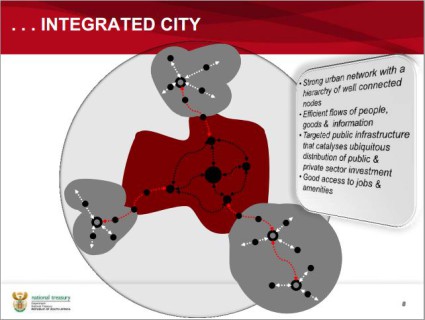

Theme 2: Area-based planning. Upgrading (brownfields development) is not the same as housing (greenfields development). Grants need to be available for communities to work closely alongside experienced urban designers, planners, architects, surveyors, engineers, transport planners to plan at the neighbourhood scale, and not individual sites for housing consolidation. At the neighbourhood scale, the metro needs to demonstrate how the UISP project will interact with other public investments in the built/urban fabric, which is guided by the Integrated Development Plan, Spatial Development Framework, the Built Environment Performance Plan (BEPP), and a number of other grants such as the Integrated City Development Grant (Treasury) and the Urban Settlements Development Grant (USDG). This also connects with Treasury’s new Urban Network Strategy, which understands the remaking of the apartheid city by means of prioritised investment in new nodes and development corridors.

National Treasury’s Integrated City Development Grant utilises the “Urban Network Strategy”

Theme 3: New tenure arrangements: The UISP is currently locked into a reverse greenfields development trajectory: people have occupied the land, they should be removed, trunk services to be installed, houses to be built, and the community needs to move back onto the land. The reality is that informal settlement upgrading is brownfields development, and the phasing of development needs to be planned in partnership with the community. Incremental upgrading means that more allocations for temporary accommodation is required. Design proposals by Cape Town based architecture firm ARG Design in respect to very dense informal settlement upgrading point to the need for “roll-over” accommodation in disruptive times of infrastructure development. The work of ISN and CORC, with partners University of Johannesburg and 26’10 South Architects on Marlboro in Johannesburg, also make proposals for upgrading in industrial areas. This also means that alternative tenure arrangements other than individual ownership needs to be further developed and local municipal officials needs training and capacity development to apply these new tenure arrangements.

Theme 4: New kinds of consolidation housing: The provision of Community Residential Units (CRU) is an option under phase 4 (housing consolidation) of the UISP and falls under Social and Rental Interventions of the National Housing Code (DHS 2009). Higher density and social and rental housing needs to be provided for, and government needs to prioritise a move away from the 40x40x40 housing paradigm: 40sqm house, 40km outside the city, where you spend 40% of your income to get to work.

Theme 5: Analysis of patterns of informality in a metro region: By having strong local design and implementation plans for individual informal settlements, patterns in metropolitan areas can be analysed. This is important to transport apartheid spatialities. It might become clear that in one metro, informal settlements are concentrated along prominent transport corridors, which might be core informants to a metro’s Transit-Orientated Development (TOD) strategies. Other areas, such as mining town, will have a very different needs and requirements for upgrading informal settlements. The link between individual settlements are the city-region might not be a UISP function, but a clear link between settlement grants (UISP, Access to Basic Services) and city restructuring grants (ICDG, USDG, Transport Grants, etc) needs to be clearly articulated for UISP is have maximum impact.

A community plan presented by Umlazi community, eThekwini

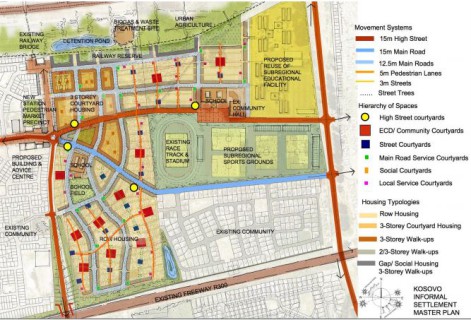

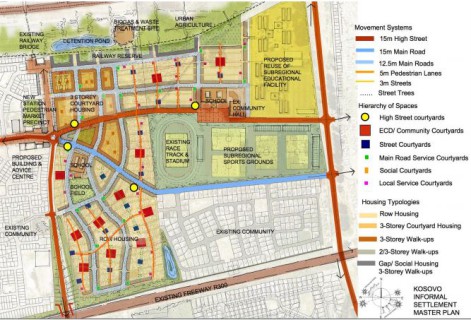

Professional layout plan design by ARG Design, Kosovo informal settlement, Cape Town

Practical recommendations:

We agree that the phased approach to upgrading is essential, and the logic and structure that the four phases of the UISP is sensible and binds the metro to a progressive and forward looking programme of action. Recommendations are made for each of the four phases:

Phase 1: Application

In addition to the listed activities:

- Increase community participation grants from 5% to 12% of subsidy quantum

- Options for new governance arrangements between communities and city officials/departments facilitated by intermediary players (e.g. NGOs)

- In their business plan, Metros need to demonstrate how UISP plans fit into public investment into the region, citing the IDP, SDF, District and Local Spatial Plans, BEPP, Integration Zones of the ICDG, and sectoral plans (e.g. Transport, Economic Development, Industrial Action Plans, etc)

- Research into the informal market for demand and supply factors of informal housing including intra- and inter “push and pull” factors

Phase 2: Project Initiation

In addition to the prioritisation of rapid delivery of interim basic services, studies commissioned, and other priorities already mentioned (typically water taps and toilets):

- Structuring of tenure arrangements (multiple options that ties back into major Land Use Management and Planning)

- Allocations for interim housing and intra-settlement relocation (ensure zero displacement)

- Set up block committees that drive local needs assessment through enumeration, profiling, spatial mapping and action planning

- Representatives of block committees serve on project steering committee

Phase 3: Project Implementation

In addition to the prioritisation of full services (trunk infrastructure, roads, amenities, etc):

- Project steering committee (read: a special task team) mandated, constituted and multi-party planning and project managing

- Line departments and formal IDP and public participation processes of the Metro needs to be aligned to the Project Steering Committee’s workplan

- Consultants appointed by the Metro to be accountable to the Steering Committee

Phase 4: Housing Consolidation

See recommendations under themes 3 and 4

In conclusion

UISP remains government’s formal response to the progressive and forward looking ideas contained in the Breaking New Ground framework document. The recommendations presented in this blog is based on a partnership approach, and recognises that structures and delegated authority and tasks are required for upgrading projects to be successful. Only when people living, using and dreaming about the future of their settlements are made to be central actors in the development process, can upgrading truly succeed.

[1] The NUSP has four main activity streams: 1) policy promotion and refinement (raise the profile of UISP and refine and improve implementation); 2) networks and forums (fill the knowledge gap and improve information flows by establishing ‘community of practice’); 3) tools and information (furnish practitioners with good practice and shared experiences over and above the guiding framework of the National Housing Code (DHS 2009)); and 4) technical assistance (help provinces and municipalities develop upgrading programmes at project level) (DPME 2010b:48).