by Ava Rose Hoffman, Yolande Hendler and Skye Dobson (on behalf of CORC)

From 7-8 April 2016, the SA SDI Alliance together with Shack/Slum Dwellers International (SDI) participated in the United Nations Habitat III Thematic Conference on Informal Settlements in Pretoria, advocating for the inclusion of the voices of the urban poor in crafting the “New Urban Agenda” (NUA).

SDI Team

The Problem of Mass Housing, The Potential of Informal Settlements

In his opening address, Dr. Joan Clos, emphasised that informal settlements and housing should be “put at the centre” politically and physically. Mass housing projects on the periphery of cities would need to be diminished because without economic activity and mixed (land) use they become dormitory neighbourhoods for the poor. Clos suggested that urbanisation needed to be used as a tool for socio-economic development through well-planned and managed cities, proposing that the following three dimensions of urbanisation need to be considered:

- The Legal Dimension (requiring new rules and regulations)

- The Physical Dimension (spatial planning and land use)

- The Financial Dimension (enabling economic design and finance)

While Clos noted that each dimension requires strategic instruments to address the “proliferation of slum dwellers”, we wonder where the “Social Dimension” featured in this discussion. The absence of shack dwellers as central agents and decision makers in planning, implementation and access to finance produces limited and brittle results. The South African Minister of Human Settlements, Lindiwe Sisulu, alluded to this effect: “We [the Department of Human Settlements] experienced challenges from time to time because we did not always understand the environment we were going in to. We are looking to adjust this legislation.” Whereas adjusted legislation carries some impact, the underlying value lies within the experience that informs strategic contributions of slum dwellers themselves.

Opening address by Joan Clos, Executive Director of UN Habitat

Where Planning Falls Short…

However, what purpose do master plans render if they are not implemented? And, how do we rethink the relationship between living spaces and workplaces? In a panel on the role of urban planning and land use, Julian Baskin (Head of Program Unit at Cities Alliance) emphasised that the urban agenda was not only about housing but how we access cities and livelihoods. Slum dwellers are no longer waiting for government, Baskin explained, but are organising themselves, forming their own plans and collecting their own data.

Slum dwellers are arriving at local governments around secondary cities saying, ‘We have our own information, partner with us’. When you have people in communities who understand plans and how to control their own development, you suddenly gain multiple planners….National governments need to build enabling legislation for cities, between local governments and communities, so that planning can be transferred to slum dwellers themselves.

Informal Settlements: Productive Centres for Resident Organising and Livelihoods

In two side events, community leaders affiliated to SDI spoke of the connection between informal settlements, livelihoods and mobilisation strategies through savings and data collection. The conversation was grounded by the very personal account of Catherine, a young mother from Johannesburg who spoke of her experience as a waste picker and recycler. In a soft, and, at moments, shaky voice, she recounted,

“I am a waste picker because this is how I support my children. This is how my mother supported us. I mainly work with cardboard and scale it every day. For 1Kg I am paid 90c.”

Catherine

Based on Catherine’s account and a further presentation by SDI partner movement, Women in Informal Employment: Globalising and Organising (WIEGO), it was evident that daily life in informal settlements significantly co-exists and intersects with livelihood activities such as waste picking, street vending and home based work. Therefore,

- Informal settlements are spaces of productivity and economic activity: homes are productive assets that contribute to economic livelihoods.

- Basic services are inputs for informal workers’ productivity and function as a direct link to livelihoods.

- Informal settlements are intricately connected to economic migrants and livelihood opportunities.

Rose Molokoane, Coordinator of FEDUP and Deputy President of SDI spoke about the broader involvement and mobilisation of shack dwellers in global discussions on development:

“As informal settlers we ask ourselves, what was achieved by the MDGs discussed twenty years ago ? Will the SDGs really attend to the needs of poor people in informal settlements? People who are planning for us without us are making a mistake. Informal settlements keep growing because most of the time we are taken as the subject of discussion without including us in the discussion… We use the power of savings and information about our informal settlements to organise ourselves, to reach out to our communities, to do something and to allow government to meet us half way” (Rose Molokoane, SDI & SA SDI Alliance)

Victoria Okoye (WIEGO) and Rose Molokoane on the left,

As a collective of global movements, WIEGO, SDI and the Huairou Commission seek to ensure that the NUA promotes inclusion and produces equitable social and economic outcomes. Some of these include:

- Recognition of all forms of work, both informal and formal

- Greater access to affordable financial services, training new technologies and decent and secure workplaces for all women and men

- Adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services

- Security of tenure for the urban poor and a stop to all forced evictions

Know Your City: Community Collected Data for Collaborative City Planning

With panelists clad in Know Your City T-shirts and the presentation of a KnowYourCity explanatory video set to an upbeat soundtrack, the mood was set for a different kind of panel. Thus far, the voices of informal settlement dwellers had been sparse in the conference. That was, until the Know Your City side event.

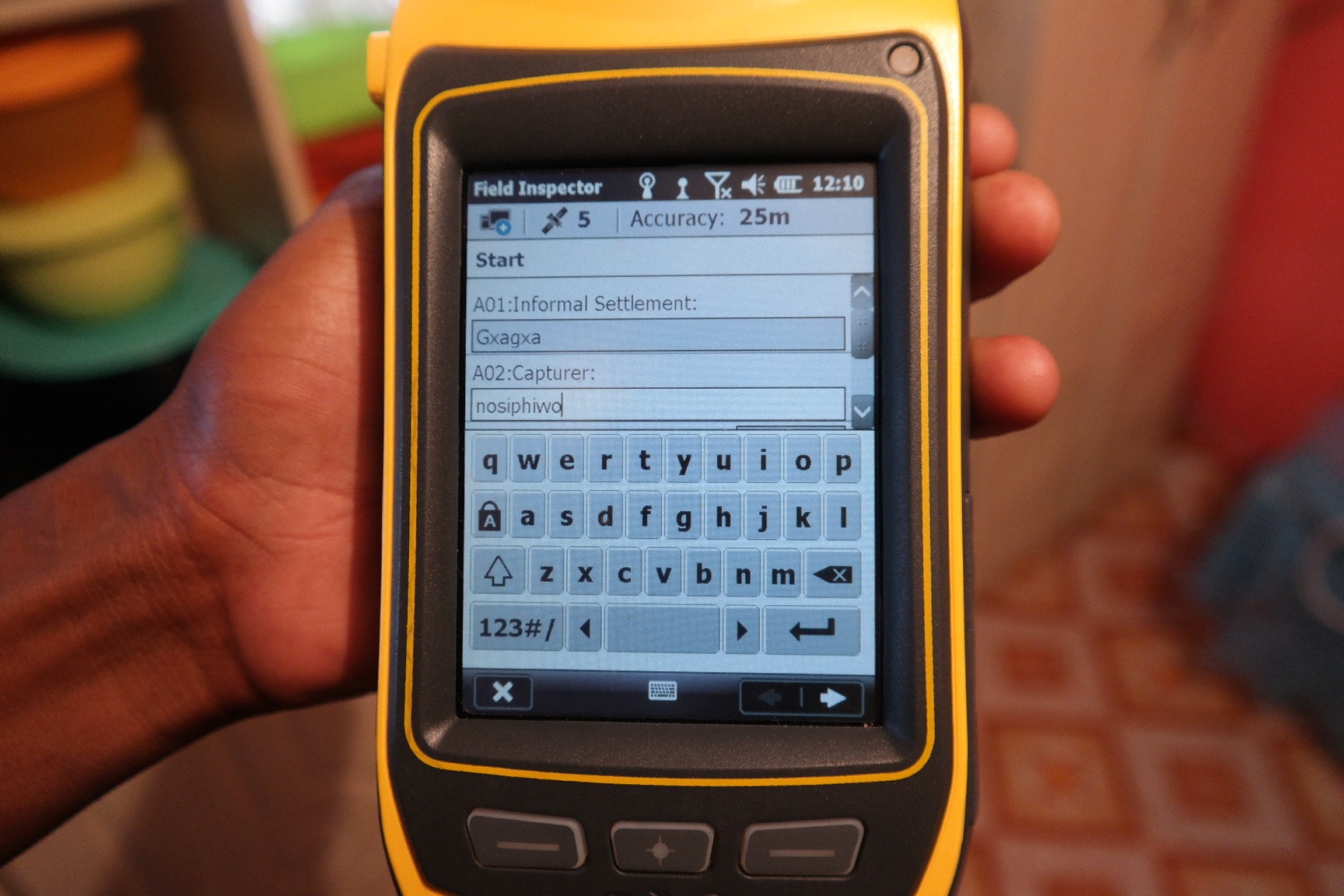

SDI’s Know Your City (KYC) campaign emphasises that the “data revolution” is central to the New Urban Agenda (NUA). It constitutes a true data revolution as shack dwellers are organised across the Global South not only to gather invaluable data on informal settlements, but to use it as the foundation for partnerships and collaborative urban planning. While “partnerships” between communities and government are widely accepted as critical to the success of the NUA, the mechanisms for actually realising productive partnerships are poorly understood. The KYC campaign has proven a highly effective strategy for catalysing such partnership and sustained dialogue between communities and government.

Mzwanele Zulu and Joyce Lungu, community leaders of urban poor federations in South Africa and Zambia, spoke of their experience profiling, enumerating and mapping their cities. Joyce spoke of the Zambian federation’s work to profile Lusaka through the strong organisational capacity in slum dweller communities. While the challenge for non-residents concerned entering and gathering reliable data, the power this information constituted for residents was evident when it was shared with government partners in the city council to identify incremental upgrading of settlements through prioritising needs and projects.

Mzwanele Zulu appreciated the large audience at the event, but gave an impassioned plea for more government officials to make the effort to attend the panels of informal dwellers. He highlighted the critical role of household level enumerations in organising his community in Joe Slovo, Cape Town. Initially, the government claimed there were too many shack dwellers to accommodate in the planned upgrade and advised on relocations to the outskirts of the city. The enumeration revealed the actual population to be far smaller and negotiations with government resulted in an agreement to undertake an in situ development. The enumeration data was also vital to the beneficiary registration process – something often mismanaged in upgrading projects, often at the expense of the poorest residents.

Joyce Lungu, Zambian Federation Leader

Julian Baskin (of Cities Alliance) reminded the audience that a tremendous change is required to create an environment that catalyses the efforts of the urban poor to improve their communities instead of simply “controlling” urban poor communities. He applauded the efforts of organised slum dweller communities in SDI to gather critical data, plan for settlement improvements and seek partnerships with government. To meet the demand of informal settlement upgrading in the Global South, partnerships that bring the efforts of a billion slum dwellers to the service of city development will be essential.

CORC Deputy Director, Charlton Ziervogel, wrapped up the discussion by explaining the process undertaken by the SDI network to standardise profiling data. Such standardisation makes it possible to aggregate data at the regional and global level which is currently hosted on SDI’s Know Your City online platform. In South Africa, FEDUP and the Informal Settlement Network (ISN) are working on two government tenders to gather data on hundreds of informal settlements in the Western Cape. Affiliates in Uganda and Kenya are making similar progress. These cases serve as powerful examples of authentic government partnership and a data revolution that chooses communities over consultants to gather data and serve as the foundation for inclusive, collaborative planning.

Know Your City Side Event

How Can we Implement Progressive Outcomes?

The two day thematic meeting ended with the adoption of the Pretoria Declaration on Informal Settlements, which is considered as official input on informal settlements to the New Urban Agenda. UN Habitat also launched its “Up for Slum Dwellers – Transforming a Billion Lives’ campaign, hosted by UN Habitat’s Participatory Slum Upgrading Program (PSUP) and the World Urban Campaign with the aim to bring about a new paradigm regarding global responses to slum upgrading.

In its current version, the Pretoria Declaration presents progressive and people-centred recommendations that relate to embracing the importance of in-situ participatory slum upgrading approaches, pursuing a focus on people-centred partnerships as suggested by “People-Public-Private Partnerships”, using participatory and inclusive approaches to developing policy, strengthening the role of local government and recognising civil society as a key actor in participatory processes. The Declaration also emphasises that the NUA should be action-oriented and implementable.

Although the declaration indicates that action should be concentrated at the local government level and that UN Habitat support to states occurs through tools such as the PSUP (See Point 9 in the Declaration), “the how” remains a strong concern for members of the South African SDI Alliance, and SDI network. While the SDI network and “Know Your City” approach was characterised by a strong presence and the message of “plan with us, not for us” was well received the mechanisms for implementation remain unclear:

“We have this beautiful constitution, but how will South African municipalities act? Politicians and officials talk very nicely – I hope that they will open doors for us when we engage them. Since I joined ISN in 2009 we are battling to sign Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with municipalities for upgrading. We only have the MoU with the City of Cape Town and eight provincial agreements with national government, but those are for the People’s Housing Process and not for upgrading. Do we know what is really happening on the ground or are we just becoming advocates of theory?” (Mzwanele Zulu, SA SDI Alliance)

“The highlight for me was making sure that our voices and messages were heard. Part of my concern was when I looked at the expenses of this event. There are a lot of people who don’t have and here is our government spending so much money on this event. But when you go and ask them to assist poor people you don’t get that response” (Melanie Manuel, SA SDI Alliance)

Watch Rose Molokoane’s input to the NUA on behalf of SDI here.