One of the main events in the calendar of the SA SDI Alliance in 2013 was the National Conference, which brought together FEDUP and ISN affiliated groups from across the country. At this 4 day conference, which was also attended by senior government officials, the two social movements made a commitment to a much closer working relationship in the context of landlessness, homelessness and urban poverty. Read more about the National Conference in this blog post.

Pre-eminence is given to the joint action-orientated charters of the two social movements, and this blog post aims to give a historical background to the emergence, peaks and troughs, and the horizon of the future of these national social movements.

The struggle years *

The 1980s was a decade marked by open conflict between the white-minority apartheid regime and a sustained mobilisation of the black majority. Liberation movements such as the United Democratic Front (UDF), founded in 1983 with the slogan “UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides”, was at the forefront of making urban space ungovernable through protests, strikes, rent and service charge boycotts, and other forms of direct and confrontational politics (Seekings 2001:21). Other marginalised racial groups such as Indians and coloureds were also centrally involved in the mobilisation against apartheid, having been displaced by major spatial reconstruction through the 1913 Land Act and the 1950 Group Areas Act. Church- and faith-based groups also played a significant role in promoting the ideals of a free and fair society, and took advantages of the slightly more lenient conditions due to recognised religious freedom.

By 1986 the beleaguered apartheid state called a State of Emergency, which saw tens of thousands of opponents detained. Movements such as the UDF, which played a role in forging a sense of unity and coherence in community based organisations (CBOs), significantly enhanced and escalated the opposition against apartheid, by that time led by exiled African National Congress (ANC) diaspora, Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and smaller anti-apartheid groupings under the banner of Black Consciousness.

uMfelandaWonye WaBantu BaseMjondolo is born *

In 1994, these savings schemes united to form the new social movement, uMfelandaWonye WaBantu BaseMjondolo, or the South African Homeless People’s Federation (SAHPF). Khan and Pieterse (2004) have further observed that the SAHPF advanced a “people-controlled development [which] is about fostering self-replicable and self-reliant social development practices” (2004:10). South Africa’s first democratic elections saw the ANC voted into power, the SAHPF was an important actor in the urban sector, uniting communities around the common struggle against homelessness, landlessness and poverty.

On 26 November 1995, President Nelson Mandela visited the SA Homeless People’s Federation. In his speech, he said

“In approaching this task we have learned a great deal from the people – from those who are the biggest providers of housing in the country, the homeless themselves. We have learned the value of partnership between ourselves and the people in their communities. We recognise the efforts but into housing by the people themselves. We are proud of the way our people use their initiative, mobilise their meagre resources, sharpen their skills, and put in their labour, in order to provide shelter for their families. Government has committed itself to supporting the people’s housing process. We will provide mechanisms and funds to support it in such a way that the standard of housing can improve – particularly for the poorest of our people”

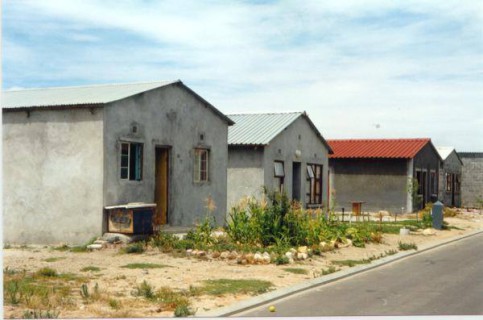

Despite the lack of “an enabling environment”, the SAHPF engaged the first minister of the Department of Housing and member of the Communist Party, Joe Slovo. At a national meeting with the SAHPF, Minister Slovo remarked, “Look here, show us the way and we will support you. We will rely on your creativity and energy. You have our hearts with you” (SA SDI Alliance 2008:9). A subsequent agreement with the National Housing Board placed the uTshani Fund as a conduit for housing subsidies. This arrangement was called the ‘uTshani Agreement’ (Ley 2009:261). Through this agreement, the Provincial Housing Board – who, at that time, was responsible as the “developer” of housing projects – paid the eligible beneficiary’s capital subsidy into the uTshani Fund, allowing the Federation to oversee implementation. This was a radical departure from mainstream housing delivery supply, in which private companies secured contracts through an open tendering process, to build the agreed number of houses (Khan and Pieterse 2004; UN Habitat 2006).

The Pledge agreement *

In the period 1996 – 2000, the Federation constructed more than 7,000 in the informal settlements of South African cities and uTshani Fund administrated more than R60 million in loans and subsidies. In the period 2000 – 2005, uTshani Fund was financially crippled, since state agencies no longer honoured the uTshani Agreement. Housing delivery slowed down rapidly, and the uTshani Fund only constructed 300 houses between 2004 – 2007 (Mitlin 2008b:20). Despite the financial constraints, SAHPF was able to demonstrate to government a compelling argument: Poor people were able to build larger and better quality houses with the same capital subsidy compared to the private sector housing contracts.

After a significant revision of the terms to which housing subsidies were allocated to the Federation, a new era broke with the Department of Human Settlements. Six Provinces signed the Pledge and those were: Gauteng, Western Cape, KwaZulu Natal, North West, Limpopo and Free State. Each of these provinces pledged to ring-fence 1,000 subsidies for FEDUP groups, tallying more than R220 million (more than US$ 30 million). The agreement stipulated that provinces would pay top structure subsidies (roughly 40% of the subsidy quantum) upfront and provide serviced greenfield plots (remaining 60% of the subsidy quantum). However, many provinces were uncomfortable with these arrangements, and in most cases, uTshani Fund continued to pre-finance loans to FEDUP groups, and retrospectively claim back subsidies back into the revolving fund.

The emergence of the Informal Settlement Network *

At the same time, a daunting realisation pressed national coordinators: “… for every Federation member with tenure security, there were another 20 without land” (FEDUP 2010:5). At this point, “the men in the Federation decided to reach out to community organisations of the urban poor, to form the Informal Settlement Network (ISN) and to use Federation capacities and [practices] to start to upgrade these settlements as well” (ibid). A series of dialogues were organised in 2008/09 starting in Johannesburg and Durban.

The growth of informal settlements over the past two decades have by far exceeded government’s efforts to deliver better services, provide adequate housing and mitigate against disasters and vulnerability. The Informal Settlement Network (ISN) has responded to the urban and land crises in South Africa by mobilizing communities around internal capabilities and capacities, and around specific settlement issues relating the incremental upgrading, tenure regularization and land. Building solidarity and unity among the urban poor, the ISN aims to creating a change process by connecting “political opportunity structures” (cf Tarrow 1996 cited in Bradlow 2013) to partnership formations with government.

The FEDUP-ISN alliance *

ISN and FEDUP have in common a shared value system and practices that build community capacity and generates knowledge. These practices are widely employed by all country federations in the Shack / Slum Dwellers International (SDI) network.

There is a reciprocal relationship between ISN and FEDUP, and the agencies and practices of the two national social movements complement one another. It is worth citing an internal concept note at length to illustrate the working relationship:

ISN networks and links communities around specific needs and issues, especially land and access to basic services. When the need arises for information gathering and savings mobilization, FEDUP moves in to establish women’s savings collectives, forge links with formal institutions and to leverage development finance. ISN plays the lead political role, which is oriented towards a people-centered engagement with a democratically-elected government” (SA SDI Alliance 2010:6).

A learning network *

Peer-to-peer horizontal exchanges are central to building networks and platforms of the urban poor. This is also the primary learning space, and communities that have generated learning on a certain aspect become “learning centers”. FEDUP and uTshani Fund’s experience in building strong local capacity to drive projects in the form of the Community Construction Management Teams (CCMTs) (Each CCMT has a bookkeeper, a procurement officer, and administration assistance and a project coordinator) could be compared to ISN “learning centres”.

| Organising dynamics | FEDUP Community Construction Management Teams (CCMTs) | ISN Learning Centre |

| Primary modality of community mobilisation | Woman’s saving schemes | Woman’s saving schemes and socio-spatial data collection |

| Governance structure | Highly organised and roles and responsibly defined | Open governance structure with undefined roles and responsibilities |

| Purpose | Project management and coordination | Learning and reflection |

| Project focus | Housing developments and subsidy allocation | Informal settlement upgrading and growing the network |

| Outcome | Effective project management and pre-financed subsidy recovery | Nodes of experience towards city-wide upgrading agenda |

Charting the way forward

The Joint FEDUP-ISN charter has special relevance for the future. Drawing on the two movements’ particular qualities has the potential to define a strong bottom-up and people-centred approach to addressing some of the most daunting challenges cities and towns face in the post-apartheid era: the growth and continued marginalisation of “informality” and the urban poor.

ISN understands its vision “to create solidarity and unity among the urban poor by building a national network in order to make the flow of resources and planning of cities more inclusive and pro poor.” ISN’s core focus areas of mobilisation (profiling), governance (establishing committees), networking (exchanges), knowledge generation (enumeration) and partnership development with government agencies creates a strong platform for sustained engagement. This process lends itself for an authentic “bottom-up agglomeration” of local community based organisations. By introducing locally responsive knowledge generating tools,

FEDUP, as a founding member of the SDI network, regards itself “an affiliate of the SDI network, FEDUP is a nationwide federation of slum dwellers in South Africa dedicated to building united, organized communities, to address homelessness, landlessness and creating sustainable and self-reliant communities led by women through informal and formal incremental human settlement upgrading.” The gendered-focus and -sensitive mobilisation by which FEDUP sets up saving schemes and CCMTs has a lot of potential to

The Joint Charter draws together the synergies created in these social movements two decades of experience. The Charter not only commits the social movements to the SDI organising principles, but also localises the agenda:

Wherever possible the skills, expertise and experience of both social movements shall be used to help further the vision, mission and goals of either movement. In practice this means the formation of joint working teams supported to sharpen and implement the agreed SDI rituals in all informal settlements of South Africa. FEDUP and ISN agree to wherever possible, conduct joint planning sessions that would allow for resources to be maximized through efficient use

The Charter ends by saying “the ISN shall strive to open up spaces within communities for FEDUP to establish new savings groups. The FEDUP shall strive to support ISN in their communities and promote the ideals of a networked movement of the urban poor”. Considering the historical narrative framed in this blog, the charters are a reminder of the part, and starts to create a roadmap for the future.

* Excerpts taken from: Fieuw, W. forthcoming. A Politics of Resolve: people-centre development in South Africa .

Selected reference list:

- Bradlow, B. 2013. Quiet Conflict: Social Movements, Institutional Change, and Upgrading Informal Settlements in South Africa. Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 23, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning. MIT

- Khan, F and Pieterse, E. 2004. The Homeless People’s Alliance: Purposive Creation and Ambiguated Realities. A case study for the UKZN project entitled: Globalisation, Marginalisation and New Social Movements in post-Apartheid South Africa. Durban: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal

- Ley, A. 2009. Housing as Governance: Interfaces between local government and civic society organisations in Cape Town, South Africa. Dr‐Ing thesis, Von der Fakultät VI – Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin

- Mitlin, D. 2008b. Urban Poor Funds: development by the people for the people. Poverty Reduction in Urban Areas Series, Working Paper 18. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- South African SDI Alliance (SA SDI Alliance). 2011a. uTshani Buyakhuluma: the grassroots are talking. June 2011, Vol.1, No. 2.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN – Habitat). 2006. Analytical Persepctives of Pro-Poor Slum Upgrading Frameworks. Nairobi